In Memoriam Abraham (Abe) Rosman, Professor Emeritus Barnard College, Columbia University (September 8, 1930 - April 13, 2020)

NOTE: The Department of Anthropology at Barnard College will host a memorial event in celebration of Abe’s life on Friday, July 3, 2020, from 1:00 to 3:00 pm EST. For more information please contact Lesley Sharp (LSharp@barnard.edu) or Maxine Weisgrau (mkw395@gmail.com).

The Department of Anthropology at Barnard College mourns the loss of its esteemed and beloved member, Abraham (Abe) Rosman, who passed away in April, 2020 at the age of 89.

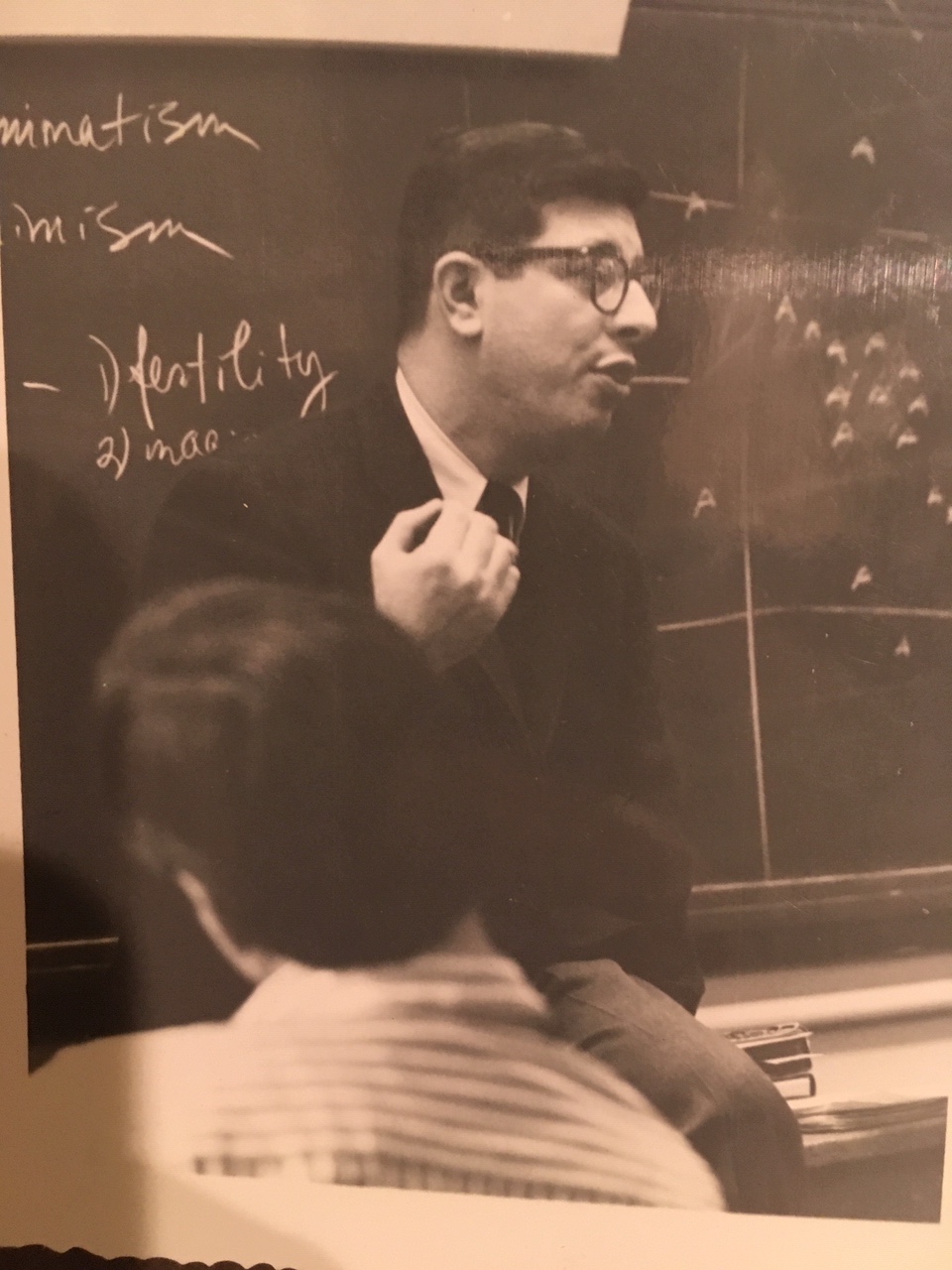

Abe has long been regarded as a foundational ancestor of sorts for Anthropology at Barnard. He joined our Department in 1962, hired by the Chair, Morton Klass, who was in the midst of rebuilding a program in disarray. Abe arrived at Barnard following short stints as an Instructor at Vassar College (1958-1960) in the Department of Economics, Sociology, and Anthropology (and where he taught Nan Rothschild, who would later join the Barnard Department); as a Visiting Faculty member at SUNY/New Paltz (Summer, 1960); and an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Antioch College (1960-1961). Abe was a lively member of our Department until he retired in 1998, continuing as an active Emeritus Professor who regularly attended scholarly events at the College, Columbia, and elsewhere throughout the City and beyond.

Abe was born in New York City in 1930 and grew up in The Bronx, near the Grand Concourse. Throughout his life, he expressed a passionate connection to his Yiddishkeit family history. His first language was Yiddish and, as a child, he attended Yiddish, and not Hebrew, school. Abe was the son and only child of Matl (Matilda; née Maud) and Manya (Emanuel) Rosman. His mother Matl had come to the U.S. from Waslikova, a small shtetl outside of Byolistok, Poland; his father (whose family name was probably Ukavitsky) from the Ukraine in what was then Russia. Manya’s work was itinerant. Both parents held seasonal jobs at the Zumeray (or Summer Ray) Hotel, a Catskills-based summer resort in North Branch, NY that was owned by Matl’s two brothers, Phillip and Zuni. The hotel catered to the far left-wing Yiddish-speaking community of New York. Phillip ran the business while Zuni worked as entertainment director, painting murals for and organizing impromptu shows (among which included satirical puppet shows) and socializing with guests.* Matl was employed as a hostess while Manya ran card games; Abe, too, would eventually work as a busboy and waiter. Abe spent much of his time as a child in the woods near the hotel, an experience that inspired within him a lifelong love of the natural world. Abe’s father died when Abe was eight years old, at which point he and his mother moved in briefly with other relatives. Matl’s employment included working as a dress cutter in New York City’s garment district, during which time she was a member of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU).

Abe attended The High School of Music and Art in New York City (later folded into what is now the Laguardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts) from 1944-1948; here he focus on visual arts and drawing. At City College (1948-1952) he earned his BA in Anthropology, followed by a brief stint in the Department of Anthropology at Columbia University (1952-1953) before he moved to Yale University (1953-1962), where he earned his doctorate in the field. Abe’s dissertation, “Social Structure and Acculturation among the Kanuri of Northern Nigeria,” was based on fieldwork conducted from 1956-1957, with support from a Foreign Area Training Fellowship through the Ford Foundation. While there, he also conducted exploratory archaeological work at Birni Ngazargamo, Bornu Province. Initially, Abe was supervised by George Peter Murdock. When Murdock left Yale in 1960 (the University had a mandatory retirement age), Abe completed his work under the supervision of Sydney Mintz, filing his dissertation in 1962 coterminous with his first year of employment at Barnard.

Abe met his first wife Bernice (née Lieberman) Rosman at Maud’s Summer Ray when she was a guest there. They married in 1951 when he was 20 and she was 18, and they lived for a time in New York. Subsequently, they simultaneously pursued and completed their doctorates at Yale. (Bernice trained as a research psychologist and later worked with Salvador Minuchin at the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic.) When Abe went to the field, Bernice accompanied him, and they lived in an Islamic Kanuri community in Bornu Province in northeastern Nigeria. Core foci of Abe’s research were the political organization of clans and acculturation in local towns, and, as he often recounted, his work was enabled by the strong support of Yurima Mustafa, a local headman. Abe was always an avid lover of animals, and during their stay in Nigeria he and Bernice kept a host of pets, including a dog, monkey, hedgehog, and baby gazelle. (Later, and once back in New York City, Abe would briefly have a pet rhesus macaque, given to him by a psychology professor at Columbia.) Abe and Bernice had two children, Lewis and Daniel (who passed away in 1991); they divorced in 1971.

Those whose association and friendship with Abe date to his years at Barnard inevitably associate him with his second wife, Paula (née Glicksman) Rubel (also known as Paula Rosman), who joined Barnard’s Anthropology Department in 1965. In partnership with Morton Klass, Abe and Paula would forge the intellectual scope and trajectory of the Department for the next 25 years. Abe and Paula were married in 1971, following their respective divorces, forming a blended family that incorporated Abe’s sons alongside Paula’s two children, Erika and David, from her first marriage. For close to fifty years Abe and Paula were inseparable collaborators who shared a keen interest in (and unwavering devotion to) a combination of Lévi-Straussian structuralism and American cultural analyses of ritual exchange, kinship relations, power, and social hierarchies. They were also avid collectors of ethnographic art, and their shared passions included North American Indian basketry, Oceanic war clubs and paddles, and Northwest Coast carvings. Their home on Riverside Drive, with walls and glass cases festooned with their collections, was also a warm and spirited hub known for its seasonal parties (whose attendees might read like a who’s who of anthropologists and collectors); smaller, informal dinners marked by lively scholarly and political debate; and relaxing afternoon teas that inevitably involved dining on warm scones.

Rosman and Rubel, as they were known in academic circles, were soon collaborating on a range of projects, their research involving brief forays to various locales, combined with historical and archival work. Abe and Paula nearly always wrote collaboratively, such that it was often impossible to parse who had written what. A pattern they established early in their career together, too, involved alternating first authorship with each new publication such that neither ever took the lead for a sustained period of time. For the remainder of their lives together, they thrived on attending annual AAA conferences (often holding court in a prominent hallway), anthropology lectures throughout New York City, auctions at Sotheby’s, and ethnographic art fairs extending from New York and Massachusetts to Paris and other European cities.

Abe and Paula began their work together by addressing potlatch along the Northwest Coast (1968), followed by a comparative examination of data culled during trips to Iran and Afghanistan (1971-72, with support from a Guggenheim Fellowship); and, subsequently, to New Guinea and New Ireland (1974). Their co-authored book-length works include Feasting with Mine Enemy: Rank and Exchange among Northwest Coast Societies (Rosman & Rubel, 1971), Your Own Pigs You May Not Eat: A Comparative Study of New Guinea Societies (Rubel & Rosman, 1978), and their well-known textbook The Tapestry of Culture, currently in its 10th edition, now co-authored with Maxine Weisgrau (Rosman, Rubel, & Weisgrau, 2017). Following their simultaneous retirements in 1998, they pursued new fields of interest, exemplified in their co-edited volume Translating Cultures (Rubel & Rosman, 2003), and Collecting Tribal Art: How Northwest Coast Masks and Eastern Island Lizard Men Became Art (Rubel & Rosman, 2012). When Rubel died suddenly and unexpectedly in May, 2018, they had just completed a new book manuscript on the social and cultural aspects of the colonial history of New Ireland (Aliens on Our Shores, n.d.).

Following Paula’s passing, Abe continued to maintain a lively social calendar with colleagues, friends, and family. A visit or meal out with Abe inevitably began with his sardonic insights on a stand-out story in that day’s New York Times, an article in a recent anthropological journal, or a bit of academic gossip. He spent his final year contentedly in independent living at Hebrew Homes in the Bronx. His passing is a terrible loss to many who have known him: Abe kept his friends close, such that many of us have known him for many decades.

Abe leaves behind him a substantial clan of his own: his children Lewis Rosman, Erika Rubel, and David Rubel; daughters-in-law Karen Guss and Julia Rubel, and son-in-law Tom Bucci; and his grandchildren Josie and Spencer Rosman and Abigail and Quentin Rubel. Although our collective sense of loss runs deep, we nevertheless choose to celebrate Abe and the indelible mark he has left on our Department and beyond. His was a life well lived, one of profound intellect, great humor, warmth, and good cheer.

___________

* For a lively account of the Zumeray see Eddy Portnoy’s essay “Modicut: The Yiddish Puppet Theater of Yosl Cutler and Zuni Maud” IN New York’s Yiddish Theater: From the Bowery to Broadway, Edna Nashon, ed., Columbia University Press, 2016.

Special thanks are owed to Lewis Rosman, David Rubel, and archival and alumni association staff of Barnard College, Yale University, City College, Antioch College, and Vassar College, all of whom offered invaluable insights and helpful details on Abe’s extraordinary life.